An upside-down view of currencies and interest rates

As headlines focus on a drop in sterling and market uncertainty following the mini-budget, we take a look from a different angle and explore what it actually means for investors.

Whatever your politics, you’ve got to admit it’s been a tough first week in the job for new UK Chancellor, Kwasi Kwarteng. Lambasted by the media, accused by the Labour leader of crashing the pound and causing higher inflation and interest rates, then a rap on the knuckles from the IMF…

It’s certainly true that sterling has been falling, and inflation and interest rates are rising. But to suggest that this is solely down to recent government incompetence is to take a very narrow view. Putting hyperbole, politics and the minute-by-minute gyrations of the market aside for a moment, let’s take a step back and look at what’s been going on.

Sterling’s woes or dollar’s strength?

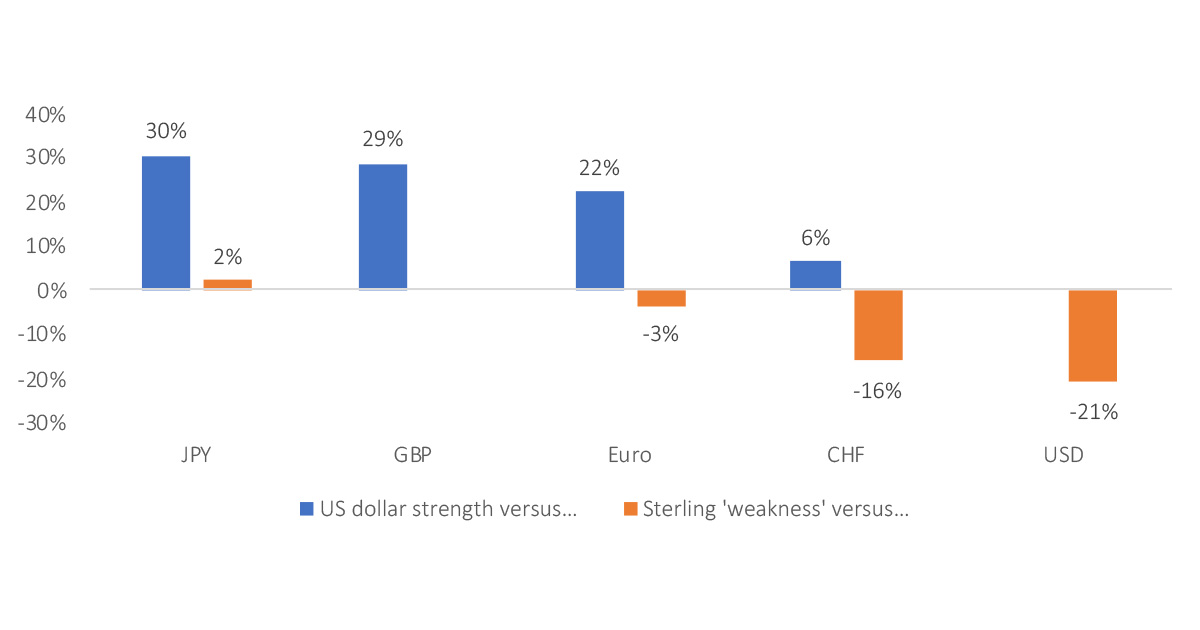

Sterling has been falling against the US dollar for some time. But flip this upside down and you’ll see that the dollar has been strengthening against sterling. In fact, due to its status as a ‘safe-haven’ currency and the Fed’s more aggressive rate raising strategy (resulting in more attractive shorter-term yields), the US dollar has strengthened against most major currencies over the past year. This attracts more global capital. It’s also a major energy exporter, which adds extra support.

The DXY index that tracks the dollar against six major currencies currently stands at a 20-year high. As the chart below shows, sterling is largely unchanged against the euro and the Japanese yen over the past year.

Figure 1: Dollar strength is the key driver of sterling ‘weakness’ – 1 year to 27 September 2022 (data: Google)

One consequence of the weak pound is importing inflation – around one third of household consumption is made up of imports, which now cost more.

Headline-grabbing claims that sterling is turning into an emerging market currency, and that this could lead to a currency crisis, are flawed for several reasons:

- The UK has a flexible exchange rate (it’s not pegged to any other currency)

- UK financial markets are highly established and liquid

- The Bank of England operates independently of the government

- Unlike emerging economies, almost the entirety of UK debt is denominated in sterling.

A silver lining for investors

From an investor’s perspective, a rising US dollar provides a positive contribution to sterling-based returns, as US assets are worth more – to the tune of over 20% – in the past year. This has helped to shore up portfolio returns for many.

The UK equity market is down only around 3% in the past year, supported by large holdings to sectors such as energy and low holdings to technology. Moreover, a majority of earnings are from overseas, which benefit to some degree from these exchange rate movements.

No one really knows where sterling will go from here and over what timeframe. But it continues to make sense right now to hedge fixed income assets, as this reduces their volatility. It’s also sensible to remain unhedged (i.e. exposed to currency movements) in equity assets, as this will support portfolio values if sterling falls further.

Inflation and interest rate rises

Again, reading the news, you might get the impression that rising inflation and interest rates in the UK is a pain inflicted on the population entirely by the government. Let’s turn this inward-looking view outward once more.

Rising interest rates are a global (not local) phenomenon, as countries grapple with high inflation caused by external influences, including:

- Rapid growth in the money supply (quantitative easing)

- Supply-side issues caused by Covid

- Price pressures on energy and food created by Russia’s war in Ukraine.

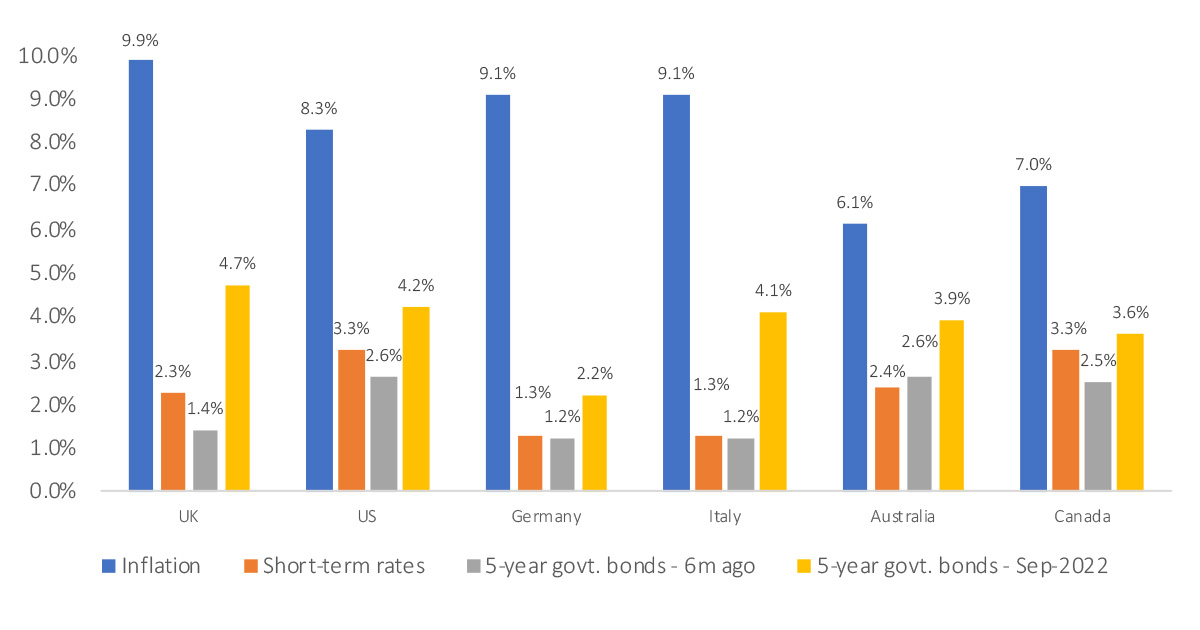

Yes, the fact that the UK government needs to borrow more for their energy cost support packages and unfunded tax cuts is also contributing to rising yields. But let’s take a look at inflation, central bank interest rates and bond yields in a number of major economies in the chart below.

Figure 2: Inflation and interest rates on 27 September 2022 Data source: Countries’ central banks (NB. inflation for Germany and Italy is the Eurozone inflation rate)

Data source: Countries’ central banks (NB. inflation for Germany and Italy is the Eurozone inflation rate)

It’s clear that inflation is universally high. Five-year bond yields (in yellow above) are now at or near 4% in all but one of these economies, and all have risen materially in the past six months (shown in grey above). While that’s bad news for mortgage holders and other borrowers, who have benefited from an extremely low cost of borrowing for many years, it’s better news for those holding cash or investing in bonds.

Despite bond price falls (as a consequence of yield rises), long-term investors will be better off, over time, from yields at 4% than at near 0%, which we saw 18 months ago. In the UK, real (after inflation) yields on index-linked gilts are now in positive territory for the first time since 2010. That’s good news for investors. As a result, investors’ future liabilities are likely to be more easily funded by their assets.

The UK’s not quite ready to fold

Some headlines have indulged a few commentators questioning whether the UK will even be able to service its debts in the future.

The UK still remains a major global economy. While the debt service burden will be increasingly heavy, it has a few things going for it. The UK still issues bonds in its own currency. It can print money to pay its debts when necessary. And it has a maturity profile with around half of its bonds maturing beyond 2030 – far longer than most major economies – reducing the short-term refinancing risks that often accompany defaults. Insurance against UK government debt default over five years implies the risk of default is negligible at less than 0.5%.

There’s a school of thought, including that of the Chancellor, that the recent support for the supply-side of the economy – increasing productivity and output by incentivising companies and entrepreneurs through tax reductions – may lead to higher rates of sustainable growth in future. This will, in turn, help to reduce inflation and allow the government to bring down debt. Obviously, this would take time. The markets currently seem unconvinced.

Keeping a level head

In essence, no-one knows how this all plays out exactly. There’s no doubt that there’ll be uncertainty ahead. But, as usual, investors who own globally-diversified portfolios of equities and higher-quality shorter-dated bonds are well-positioned to weather any possible storms.

As we’ve seen, the view from a bat’s perch can provide useful perspective in a world full of politicians, central banks, economists, pundits and active investors all bumping around in the dark.

‘This too shall pass!’, as the late, great John C. Bogle used to constantly remind investors.

At Goodmans, we maintain a sensible, evidence-led, long-term approach to investing that doesn’t falter when headlines get spicy. If you'd like to book in a financial planning review, give us a call.

This article is distributed for educational purposes and should not be considered investment advice or an offer of any security for sale. This article contains the opinions of the author but not necessarily the Firm and does not represent a recommendation of any particular security, strategy, or investment product. Information contained herein has been obtained from sources believed to be reliable but is not guaranteed. Past performance is not indicative of future results and no representation is made that the stated results will be replicated.